The imperative of domestic resource mobilization

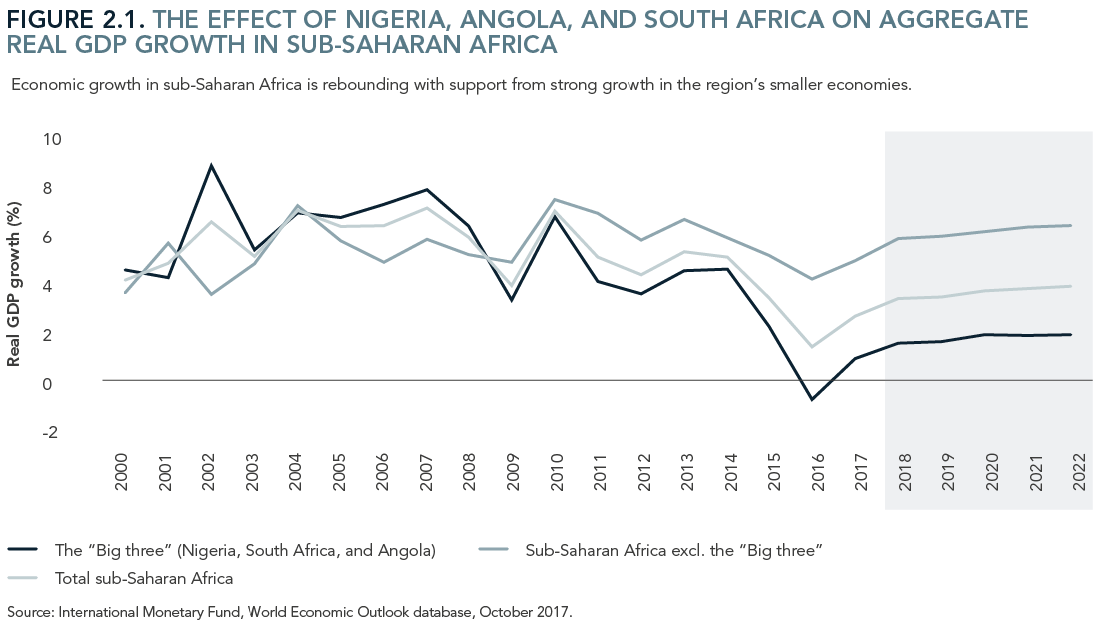

In 2018, the economic outlook across sub-Saharan Africa will continue to improve as the non resource-intensive economies expand at solid rates while the resource-intensive ones consolidate recoveries from the 2014 terms of trade shock. The latest projections have the region’s aggregate gross domestic product (GDP) growth rising further this year, albeit at a subdued 3.4 percent rate, from a trough of 1.4 percent in 2016. Thereafter, growth strengthens to almost 4 percent by 2022.

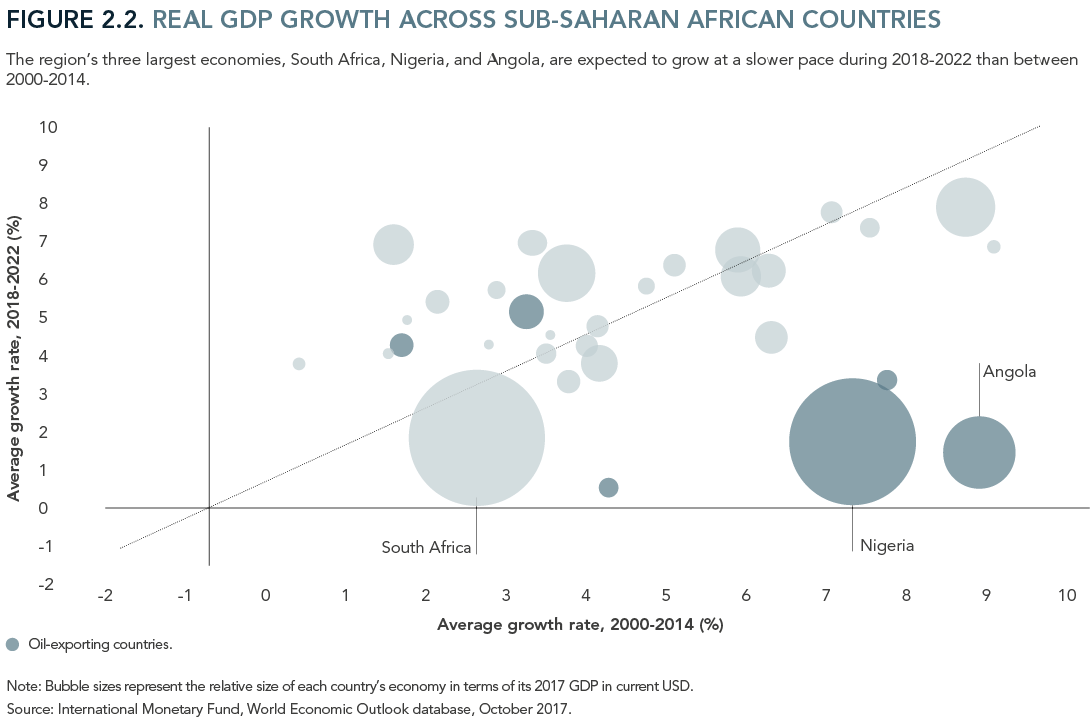

Half of the economies in sub-Saharan Africa will expand over the next five years at an average rate similar to or higher than the rate that prevailed in the heyday of the “Africa rising” narrative.

This aggregate contour masks significant differences across countries. Importantly, the recovery will remain tepid in Angola, Nigeria, and South Africa, the continent’s largest economies with growth averaging under 2 percent—which is below the rate of population growth—over the next five years. These large economies are at risk of a lost decade unless policymakers implement significant reforms to shift the growth model away from excessive reliance on oil in Angola and Nigeria and, in the case of South Africa, to overcome structural problems—many inherited from the apartheid era.

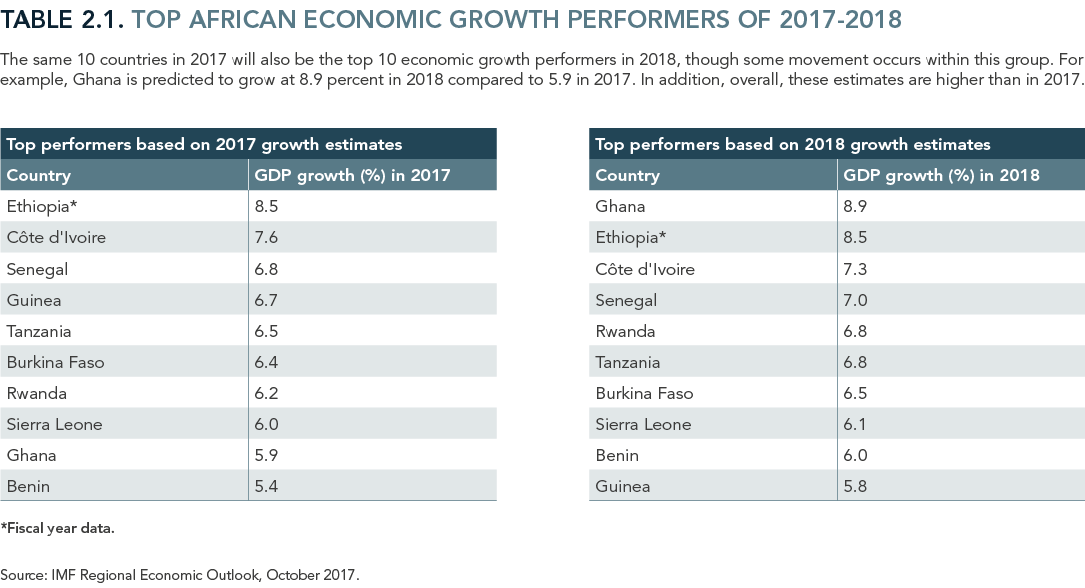

Excluding these large economies or focusing on the country-level growth rates reveals a significantly brighter outlook. Aggregate growth for the region rises to 5 percent in 2018 and reaches 6.4 percent by 2022 (Figure 2.1). About half of the world’s fastest-growing economies will still be located on the continent, with over 20 economies expanding at an average rate of 5 percent or higher over the next five years, faster than the 3.7 percent rate for the global economy. Ghana, Ethiopia, Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal, Rwanda, Tanzania, Burkina Faso, Sierra Leone, Benin, and Guinea will continue to be the top-10 performers this year, respectively. Importantly, as shown in Figure 2.2, half of the economies in sub-Saharan Africa will expand over the next five years at an average rate similar to or higher than the rate that prevailed in the heyday of the “Africa rising” narrative between 2000 and 2014, suggesting that it might be premature to call for end of the region’s economic promise.

Even with relatively bright economic prospects in several countries, the challenges facing the region’s economies are daunting, particularly in the financing environment. Sustaining the economic momentum or, in the case of oil exporters, regaining it will require more efforts from their governments to mobilize domestic resources as external financing conditions will prove more difficult.

Revenues from commodity exports will still lower in 2018

First, the relatively subdued outlook for several commodity prices will deprive many countries of vital export earnings to help finance their economic agendas. Although commodity, notably oil, prices have stabilized and generally been on the rise since 2016, they are projected to remain below pre-2014 levels, and the adjustment of oil-dependent economies to lower oil prices is still incomplete. These economies will continue to experience balance-of-payment pressures and loss of fiscal revenues. The necessary fiscal consolidation to preserve macroeconomic stability will entail further cuts in spending and require larger financing from alternative sources to sustain growth.

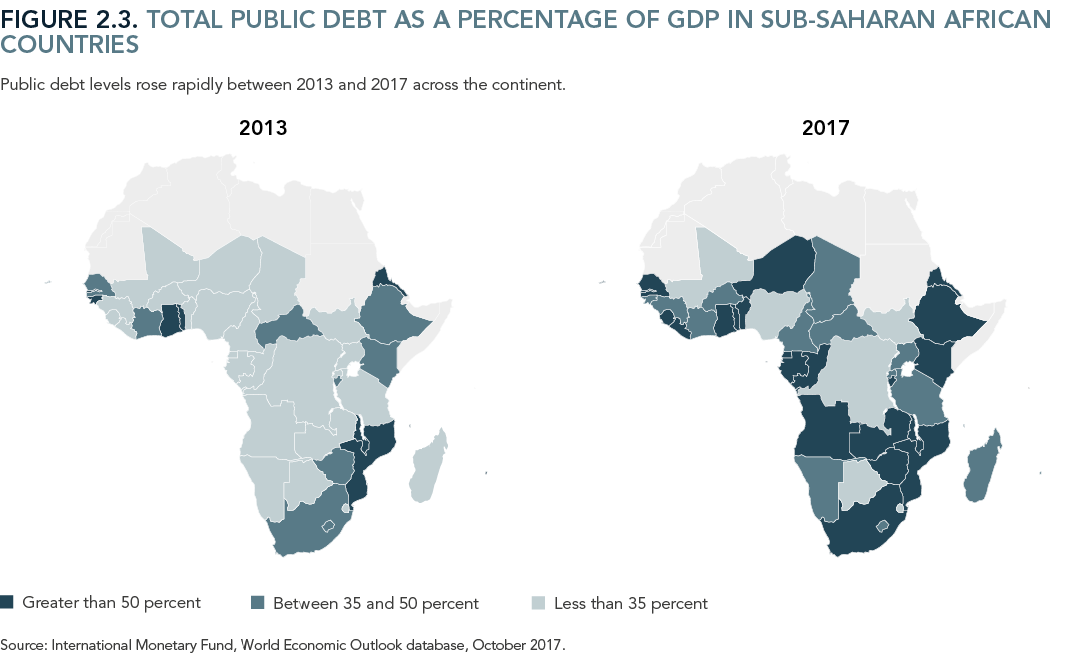

Rising public debt limits continued reliance on debt financing

Second, the scope to issue public debt to finance economic development will be more limited. Government debt, which has been an important source of financing, has risen rapidly and is now approaching critical levels in some countries. The average public debt as a percent of GDP rose from 40 percent in 2013 to an estimated 56 percent in 2017, and debt levels now exceed 50 percent in 25 of the 45 sub-Saharan African countries, compared to just 11 in 2013 (Figure 2.3). Debt service ratios have also risen rapidly. The median debt service-to-revenues ratio in the region increased from 5 percent in 2013 to an estimated 10 percent last year; it is particularly high in oil-dependent countries where it likely exceeded 25 percent in 2017. Amid concerns about debt sustainability and other risks, several countries across the continent with sovereign ratings were downgraded over the past year, which puts upward pressures on external financing costs.

African economies remain vulnerable to tighter monetary policies in advanced economies

Third, the outlook for monetary policy in advanced economies points to continued reduction of policy stimulus. In 2017, the Bank of Canada and the Bank of England joined the Federal Reserve in reducing monetary policy accommodation. This year, the European Central Bank is expected to join its peers. A synchronized reduction of monetary policy accommodation in the advanced economies could push up global interest rates, resulting in a rapid increase in the cost of external financing for African economies. Moreover, an important and worrisome feature of the debt accumulation is the dominance of external debt, particularly that denominated in foreign currency. As monetary policy accommodation is reduced in the advanced economies, it could also contribute to depreciations of local currencies across sub-Saharan Africa against hard currencies and further raise debt ratios and debt servicing costs. A policy priority in 2018 should be to ensure that the debts are sufficiently hedged against both currency and interest rates risks.

the future of overseas development assistance is becoming more uncertain

Finally, the outlook for overseas development assistance, which has been an important source of financing for some countries, is increasingly uncertain. Discontent with globalization and changing political environments are causing governments in some advanced economies to revisit their commitments to development assistance. In some cases, large portions of funds earmarked for development assistance are being reallocated to more immediate humanitarian needs.

it is imperative that africa mobilizes more domestic resources

The challenging external financing environment due to these various factors underscores the imperative for African countries to step up domestic resource mobilization efforts to help finance economic agendas more sustainably.

Most sub-Saharan African countries suffer from perennially low domestic saving rates, which average just 15 percent of GDP—among the lowest in the world. These low saving rates fall significantly short of financing needs. Based on projections in the International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Outlook, the saving rates on the continent will remain around 15 percent over the next five years, while investment rates will average 21 percent of GDP. This trend suggests an external funding gap of 6 percentage points of GDP. In reality, the financing needs gap is even wider because historical experience suggests that countries at this stage of economic development need investment rates close to 30 percent of GDP or higher over a sustained period to achieve economic transformation. At the desired investment rates, the funding gap rises to 15 percent of GDP, which amounts to an annual funding gap of about $275 billion. Filling this large void with external financing alone will entail substantial current account deficits and make the economies prone to balance of payment crises and macroeconomic instability. This conundrum highlights the importance of boosting domestic saving rates. The good news is that, across Africa, the scope for domestic resource mobilization is great.

There is room to boost tax revenues

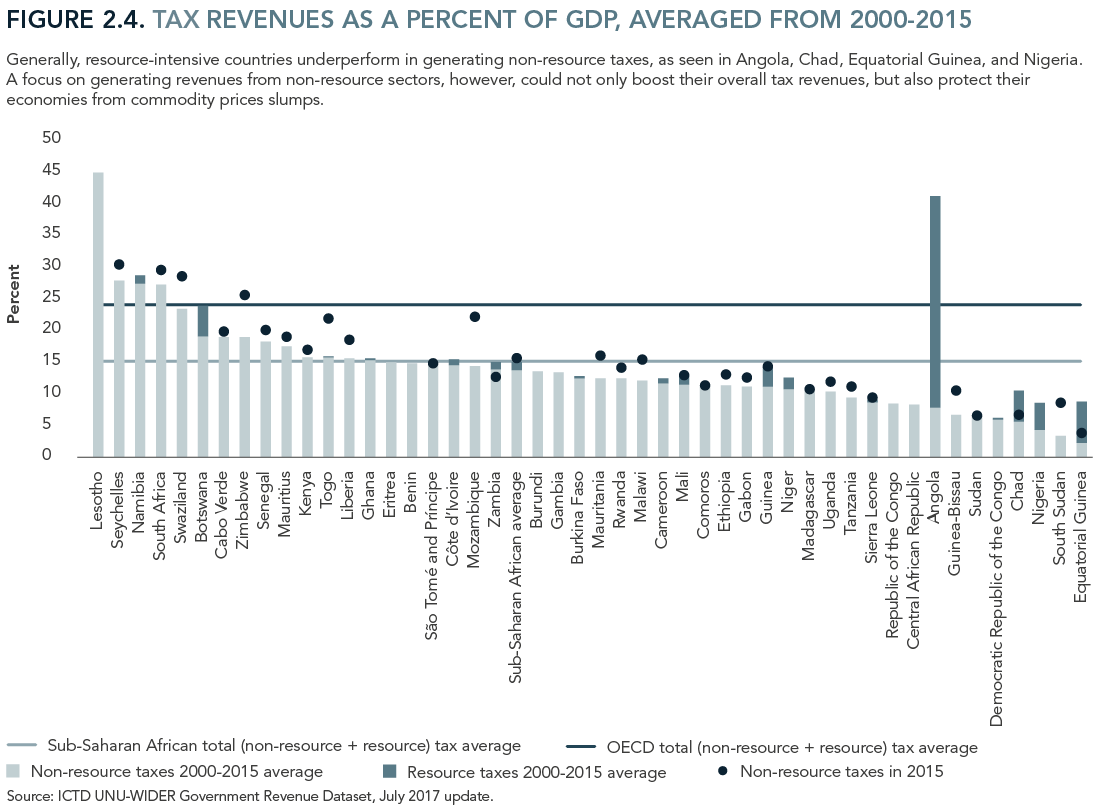

First, tax revenues are low. This state of affairs reflects not only the region’s prominent informal economy, but also inefficiencies in revenue collection. Average tax revenues (excluding social contributions) stand at about 15 percent in sub-Saharan Africa, compared with 24 percent in OECD countries (Figure 2.4). For several economies, revenues are below 10 percent of GDP. Non-resource tax revenues are particularly low in some resource-intensive economies, suggesting there is scope to mobilize more revenues from the non-resource sectors. For example, in Angola, Chad, and Nigeria, revenues from non-resource sectors are only about 5 percent of GDP. The excess reliance on resource revenues exacerbates the effect of declines in commodity prices on these economies. In contrast, Lesotho, Namibia, Seychelles, South Africa, and Swaziland have been more successful, with revenue collection comparable to or even exceeding the OECD average. The lessons learned from these countries may provide useful guidance to others striving to promote tax revenue mobilization.

Countries must more efficiently manage natural resources wealth

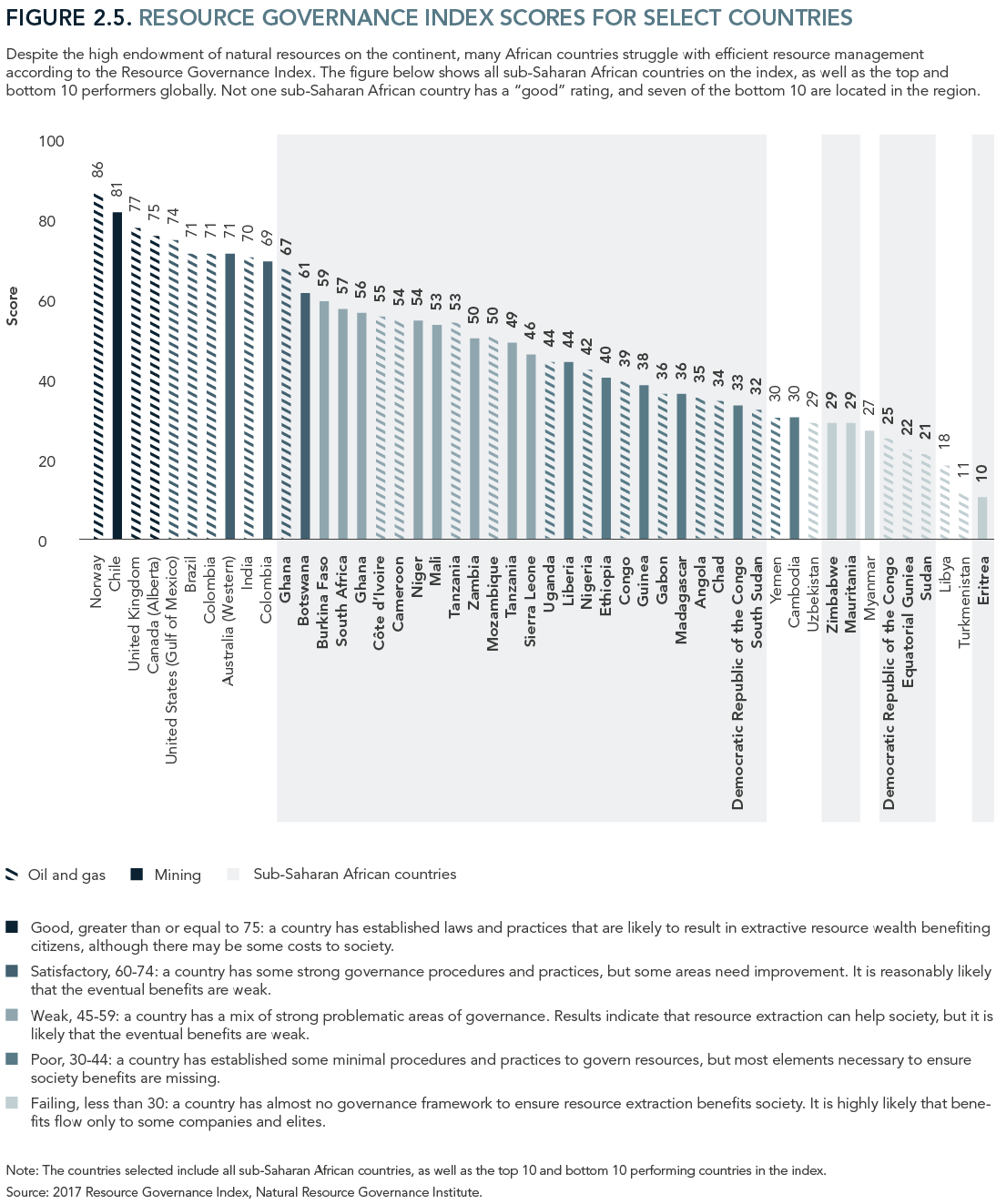

Second, the continent is endowed with vast amounts of natural resources. Yet, these domestic resources are generally not managed efficiently. The most recent Resource Governance Index indicates that no sub-Saharan African country has a “good” rating in natural resource governance, and only Ghana and Botswana have “satisfactory” ratings (Figure 2.5). All other countries have “weak” or “poor” ratings, and seven of the world’s bottom 10 performers with “failing” governance scores are in Africa, including the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, and Zimbabwe.

Leaders must heighten efforts to combat illicit financial flows

Third, an estimated $50 billion or more per year is lost to illicit capital outflows, roughly equivalent to the net official development assistance flows to the region in 2015. These illicit flows deprive economies of important domestic resources and should be halted (see Figure 2.6). Effectively curtailing them will require great determination from governments and civil societies as well as cooperation of other countries outside of Africa where these funds are invested. The savings pool of the African diaspora, including remittances and diaspora bonds (see Michael Famoroti’s viewpoint in this chapter), could also be important and reliable sources of financing, and governments should explore ways to facilitate the mobilization of these resources.

Leverage technology to enhance domestic revenue mobilization

Domestic resource mobilization can also be greatly enhanced through continued development of financial sectors to offer more instruments to incentivize private savings and through financial inclusion to reduce informality. Advancement in technology presents opportunities for governments to do so. For example, earlier in the year, Kenya offered the world’s first mobile-only retail bond with a subscription level as low as $30 and a coupon rate of 10 percent (see Chapter 5 for a more in-depth discussion on this new tool). The bond, which was taken up mainly by small savers, allowed the government to tap into a new pool of funds and low-income Kenyans to earn interest on their savings. Technology also provides an opportunity to enhance revenue, modernize and streamline tax collection processes, seal leakages, and boost revenues. In Ethiopia, for example, the adoption of electronic sales register machines since 2008 has led to significant increases in reported sales and tax payments.

In sum, a more difficult external financing environment lies ahead for African countries, precisely at a time when financing needs for economic development—especially to gain traction on the Sustainable Development Goals—are growing. Efforts along all fronts to boost domestic saving rates will go a long way to narrow the funding gap sufficiently for external financing to fill the remaining void without compromising macroeconomic stability. In addition, governments should resort more to innovative financing mechanisms, such as blended finance or public-private partnerships and other risk mitigation mechanisms, to crowd in more private sector investment and help preserve the solvency of public sector balance sheets.